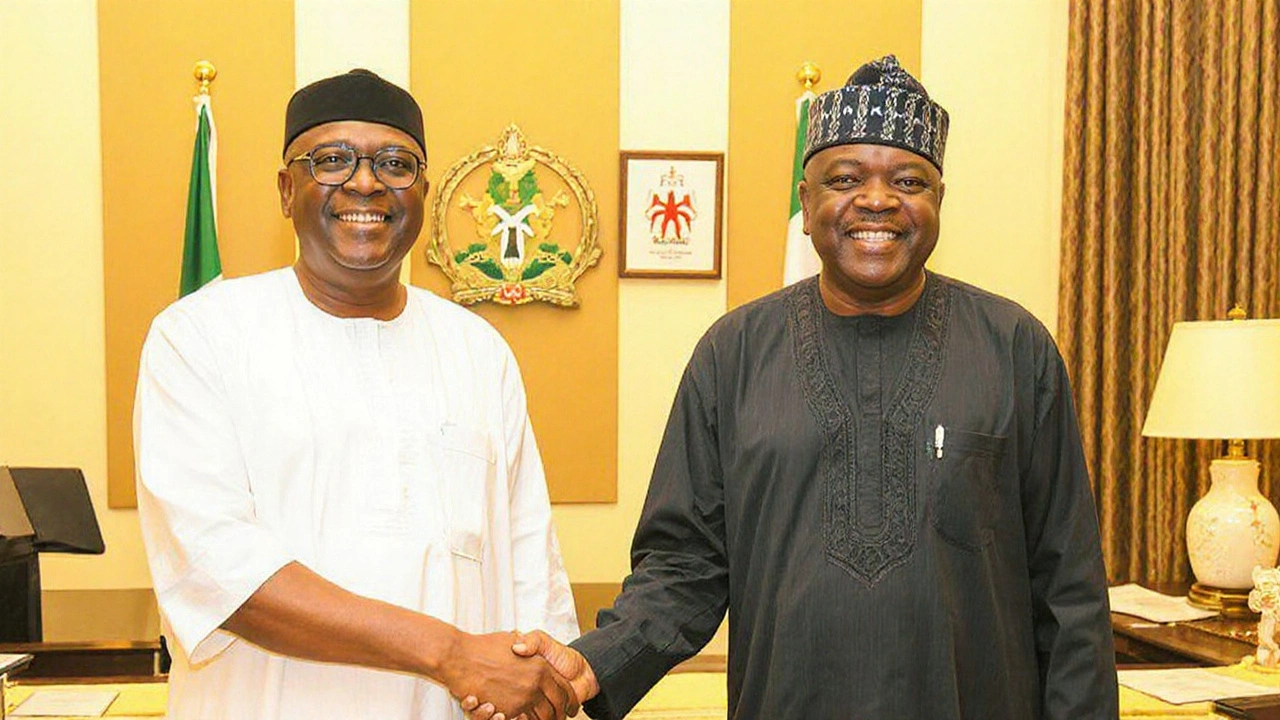

On September 22, 2025, Rivers State Governor Siminalayi Fubara stepped into the Presidential Villa in Abuja for a private audience with President Bola Tinubu. Dressed in a white caftan and black cap, he arrived at 6:22 p.m., his first official visit since the federal government lifted the emergency rule that had suspended his administration for six months. In a brief press briefing after the meeting, Fubara announced that he and his predecessor, former governor and current FCT Minister Nyesom Wike, have made peace and will now collaborate on the state’s development agenda.

Background to the Crisis

The rift that led to the emergency began shortly after Fubara’s inauguration in May 2023. Disagreements over control of state resources, appointment powers, and political patronage pitted the young governor against Wike, who still commands a powerful faction within the state’s ruling party. The feud quickly spilled into the Rivers State House of Assembly, fracturing legislative cooperation and halting several key infrastructure projects.

By March 2025, the tension escalated to the point where President Tinubu invoked his constitutional authority, suspending Fubara, his deputy, and a majority of the assembly members. Retired Admiral Ibok‑Ete Ibas was installed as sole administrator to restore order. During the six‑month emergency, budget approvals stalled, oil revenue allocations were delayed, and community projects across Port Harcourt and the hinterland fell into limbo.

In June, Tinubu convened a high‑level meeting with Fubara, Wike, and other stakeholders, signaling a possible thaw. Yet the underlying mistrust lingered, and both leaders continued to maneuver for political dominance, leaving the state’s governance in a precarious balance.

Implications of the Reconciliation

Fubara’s declaration of peace carries immediate practical effects. First, it removes the political deadlock that has crippled the State House of Assembly, allowing bills on health, education, and infrastructure to move forward. Second, it re‑opens channels for federal assistance; with Tinubu’s backing, Rivers can now expect the release of previously withheld development funds.

Local business owners have welcomed the news, citing renewed confidence that oil‑related projects—such as the refinery expansion in Eleme and the ongoing Port Harcourt urban renewal—will resume without further bureaucratic snags. Community leaders, too, see an opportunity to address long‑standing grievances over land allocations and environmental remediation now that the two most influential state figures are ostensibly aligned.

From a national perspective, the reconciliation underscores Tinubu’s role as a political arbitrator. The president described the meeting as a "father‑to‑son" conversation, emphasizing guidance over coercion. By facilitating a settlement, Tinubu not only stabilizes a crucial oil‑producing region but also signals to other states that federal intervention can yield collaborative outcomes rather than perpetual conflict.

Critics, however, caution that rhetoric alone may not translate into lasting change. Observers point to past instances where public peace accords collapsed under the weight of entrenched rivalries. The true test will be whether joint initiatives—such as the promised road rehabilitation program and the reboot of the Rivers State University research facilities—materialize within the next few months.

For now, the atmosphere in Port Harcourt reflects cautious optimism. Streets that once echoed with protests over stalled projects are seeing renewed activity as contractors mobilize and civil servants return to their offices. Residents, still bearing the scars of a prolonged governance vacuum, are watching closely to see if the promised "working together for development" becomes more than just political theater.

September 28, 2025 AT 02:15

It’s like watching a Shakespearean tragedy where the villain and the hero shake hands in the final act-except this time, the stage is flooded with oil money and half-built bridges. There’s poetry in the absurdity, honestly. The real drama isn’t the meeting-it’s whether the people who’ve been waiting six months for clean water or a working hospital get anything at all. Let’s not turn reconciliation into a photo op with a press release and call it a win.

September 28, 2025 AT 04:13

Man i just hope this means the kids in Obio-Akpor can finally go to school without walking through mud up to their knees again. Tinubu playing dad here kinda hits different. Like maybe sometimes leaders just need to sit down and talk instead of throwing tantrums and suspending governors. I dont know maybe im too soft but i believe in second chances. Let the money flow and the asphalt lay

September 28, 2025 AT 19:43

This is all performative. Wike controlled the state for 12 years. Fubara was never going to win. The emergency was just a pause button. Now they’re pretending to collaborate because Tinubu told them to. The same people who stole millions are now holding hands. Don’t be fooled. The refinery expansion? It’s been on paper since 2019. Nothing changes until someone goes to jail.

September 30, 2025 AT 17:35

This is the end of Nigeria’s last shred of dignity. Two men who turned a state into a war zone now pretend to be brothers. The people starved while they played chess with budgets. The children died waiting for ambulances. And now we’re supposed to clap because they smiled at a photo op? No. This isn’t peace. This is a funeral march in a white caftan.

September 27, 2025 AT 11:33

Yessss this is the energy we needed! 🙌 Finally some grown-up politics in Rivers. Hope this actually sticks and the roads get fixed before the next rainy season. I’m so tired of seeing Port Harcourt stuck in limbo.